Memory of sisters Whitney and Shari Ruzzi

Interview with Emiliya Ether

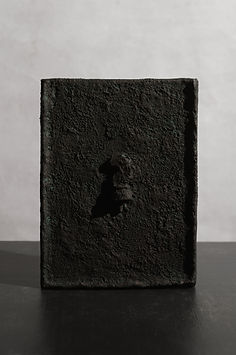

“A cup of tea has always been a symbol of our connection with grandma. We called her Bomma — the Dutch word for grandmother. When we were kids, we were often in the kitchen with her. She would make us tea and ask about what was going on in our lives. We would sit around the table and talk. She got sick and died a few years ago, during COVID. It was really difficult for us because we weren’t allowed to visit the hospital and say our goodbyes. Shari struggled with that a lot. After Bomma passed away, Shari couldn’t look at her pictures or put them up in the house — it felt too confronting. So she asked me to create an artwork to remember Bomma by. I had all this tea because, when Bomma got diagnosed with cancer, she came to visit me in Mallorca, where I’d moved. She was a woman who never left her house and she was so sick, but she flew all the way from Belgium to see me. She brought me a suitcase full of tea, and every time I drink it, I think of her. I used those tea leaves to create the artwork. When I think of Bomma, I realize how strong she was — always in service to everyone: helping, cooking, cleaning. After the doctor said she had two months to live, she lived for another two years. She got on the plane to come see me when she should have been in a wheelchair. She was still being that wife, that mother, that grandmother. She was pushing and pushing. That was the first time I saw the strength of a housewife and how capable women are. Bomma showed me a completely different side of womanhood that I didn’t understand or value as a kid. With age, I’ve come to realize how difficult it is to take care of everything and everyone and how much it does for others without them realizing it. In a really subtle way, Bomma taught us a lot about love and life. She showed us the importance of being present with loved ones by just being there for us. That’s why we created Oon — to honor precious moments and connections through artworks that hold personal stories.” Written by Emiliya Ether

Memory of Elena Vasilieva

Interview with Emiliya Ether

“My granddad was born in 1933. There were two kids in the family — him and his younger brother. When my granddad was 8 years old, the Second World War started. The city that his family used to live in — St. Petersburg, Russia (Leningrad, the Soviet Union, back then) — was occupied for two and a half years. It was completely paralyzed — nothing and nobody could go in or out. The people who stayed there could only survive on the resources and provisions left in the city. Because of the extreme conditions and hunger, my grandfather’s little brother and mom passed away — they couldn't make it. That was the turning point when my great-granddad decided to flee with my grandfather. The only way out of the city was through Ladoga Lake — one of the biggest lakes in the world. It was winter, and the water was frozen. Crossing the lake on foot probably took them a few hours or even a night. My grandfather had already been very weak at that point — he couldn’t move or do anything. He was barely breathing. He was lying on a sledge, and his father smuggled him out of the city. They got on the train and traveled far east — 800 kilometers away, where there wasn't much military activity. The moment they arrived in the other city, they went to the hospital. The doctors weren’t sure if my granddad would make it through the night — they said he would probably pass away within a couple of days. But he did make it. His whole life he lived in that city — Nizhny Novgorod — where I was born. He was doing well growing up, but at some point, when he was a teenager, he started noticing that the lines in books would get blurry when he tried to read. He wasn’t paying much attention to that at first, thinking it was a temporary thing. But his sight got worse and worse. So his father took him to the doctors — they said that it could have been a side effect of what had happened previously or it could have been something else. Either way, they couldn’t do anything about it. When I was born, my grandfather could still distinguish between day and nighttime, but after a few years, even that faded away. He completely lost his sight. Essentially, he has never seen me, but we had such a special bond. We were always together. We would often go in the city — he would hold my hand around the elbow, and I would guide him. He would tell me stories while we were walking around the parks. We would listen to audiobooks on the radio, and he would play the accordion for me. He did a lot with his hands — I could observe him putting together shelving or doing anything else around the house for hours. And he loved playing chess. He was absolutely brilliant at it. Though the only way for him to play it was to have a chess board with holes in every square and to use chess pieces with little tips to insert them with. To make a move, he would need to feel the figures on his side of the board, then on the opposite side. He had to remember the actual layout as well as the previous moves. Only now do I realize how crazy that must have been, but he did it so effortlessly — just like everything else. That's the biggest lesson I've learned from him — to keep going no matter what. He never complained or argued with anyone. He was the calmest person I’ve ever known — very accepting of the way his life turned out. He always tried to do his best and not to limit himself. And even though he’s no longer around, I still feel his presence. I feel that he’s still here. A connection like the one that we shared doesn’t just go away. It stays with you.”